Welcome to StoP and get a first impression here of what StoP is all about. We are a committed voice in the fight against everyday, massive patriarchal violence using our neighbourhood-based community work. Our focus is on domestic violence that affects women worldwide. What we want to achieve: social change from the bottom up and loving, equal relationships through the mobilization of empathy and support of civil society in local communities.

Select your language

StoP mission

The StoP concept originates from Germany and the abbreviation stand for “Stadtteile ohne Partnergewalt”. In English: “(Local) Communities without intimate partner violence”. This expresses our main mission: to stop and prevent violence in intimate partnerships, often referred to as domestic violence.

StoP focuses on the prevention of patriarchal violence against women and people who move outside traditional gender norms. A common form of this violence is the exercise of power and control in close social relationships through physical, sexual, psychological, economic and social assaults.

This violence does not take place in a vacuum: neighbours, friends or colleagues suspect, hear, see something. They may be indifferent, think it is none of their business or that it is normal to treat women in this way. But more likely, they want to help but don't know how, and this makes them feel insecure or afraid to intervene. This is StoP's starting point – we mobilise the support and change potential of neighbourhoods and civic society.

Studies show: attitudes and actions of the people around victims can make a real difference, they can save lives, interrupt and stop violence! That is why StoP aims to educate and empower communities at a local level. Communities can play a significant role in ensuring that violence against women/queer people is no longer tolerated or ignored. The StoP logo with the bell button symbolises our idea of getting involved, helping, in other words: ringing the bell!

The goal is the same: to end violence against women. However, these audiences are diverse – which means that the toolkit is designed to be as accessible as possible. There is also a public and an internal section. The internal section contains further tools and resources that are more advanced and should not be used without the knowledge gained from the StoP training.

The „Bell Bajao” campaign from India was a great source of inspiration!

StoP improves safety and promotes respectful, loving and truly equal relationships. To achieve this, we aim to 1) increase the willingness of victims and perpetrators to come forward, break the silence and seek help, and 2) systematically build the will and skills for community mobilisation and social change at the grassroots level.

We believe that preventing domestic violence and building supportive social relationships will reduce violence in general. In the long term, StoP's work can contribute to a more democratic society where all genders are equal and no one suffers violence or discrimination.

Say something. Do something. That's the power of StoP's guiding principle, which sums up what works against violence.

The change that StoP is bringing about

Neighbours turn down the TV and listen to the screams and banging coming from the flat next door. They ring the doorbell of this flat and ask if they can borrow a charger for their mobile phone, thus interrupting the violence. They call the police. They set up a telephone chain to support a woman experiencing violence. They offer her shelter. Someone helps to make this neighbour's front door 'burglar-proof'. They meet up with other neighbours in the shopping centre and inform them about domestic violence. The daycare centre invites them to talk about the topic at the parents' evening. Caretakers distribute StoP information leaflets and stickers on front doors and letterboxes, and also hang posters on the housing association's information board. The school integrates the topic of partner violence into lessons. The community centre offers de-escalation training. Men meet with men, talk about violence and discuss what can be done to prevent it. The hip-hop group from the youth club makes a rap in which the words “Violence Protection Act” booming out of the speakers. Women get together, form a group and organise the escape of a neighbor to a women's refuge. A woman from the StoP group organises Tupperware parties and every time before she starts tupping, she talks about the topic, distributes flyers and promotes StoP. A StoP poster with the numbers of women's shelters and advice centres hangs in the window of the grocer's shop and at the hairdresser's, the pub and the doctor's office, too. In addition all local business and numerous associations in the neighbourhood receive the declaration that partner violence is not a private matter and will not be tolerated. Sexist advertising doesn't stand a chance in the neighborhood, it is pasted over, painted over... in no time at all. Women no longer hurry through the stairwell wearing sunglasses because they are ashamed of their abuse, but ring the neighbors' doorbells and ask for advice. Transgender and queer neighbours feel safe. They know they will be met with understanding and support and not helplessness or even sexist comments. Domestic violence becomes a public issue. Local social networks become a resource for empowerment and sustainable social change.

“Is this just a utopia? Nah, it's not! We can all make a difference, and we can do it together.”

StoP Rationale

Since the women's movement in the 1970, much has been done to combat violence against women and to support those affected. But: It's not enough! Why?

- In the words of UN rapporteur Dubravka Šimonović: "Recently, both at the regional and international level, we have witnessed an increased awareness of women's rights but also the persistence of gender-based violence against women and girls across all layers of society" (2019, n.p.). The prevalence of violence remains high. Violence against women is the most common human rights violation: “Whether at home, on the streets or during war, violence against women and girls is a human rights violation of pandemic proportions that takes place in public and spaces” (UN Women 2019, n.p.). In Germany, for example, a woman is killed by her (ex-)partner almost every third day and there is an attempted murder every day. And that's just the tip of the iceberg (BKA 2023: 14, IMK 2023: 9). The situation is similar in other countries.

- The gap: there is not enough professional support available, and when there is, the barriers to accessing specialist services are often too high. There is a lack of information, fear, shame, distrust, poverty. For example, 67% of victims did not report the most serious incident of intimate partner violence to the police or any other organisation (FRA 2014).

- Most of the established interventions tend to be effective only after the violence has occurred. The specific context of the crime and the potential of neighbours, friends and communities are neglected. Yet studies show that community norms and the quality of the local social context reduce intimate partner violence, lower the rate of femicide and promote equality in partnerships. Where community efficacy is strong and women have more friends, they are more likely to disclose and seek help (Browning 2002, Gloor/Meier 2022). Neighbours have the advantage of short distances. They can be reached quickly in crisis situations. They are usually directly or indirectly involved (hearing, seeing, suspecting...) and sometimes feel directly affected (anger, fear, irritation, concern, empathy). They can help prevent escalation and stop violence! They can offer support in everyday life and provide information about what is available.

- The Istanbul Convention calls for such work; it emphasizes the importance of prevention and civil society and states that violence against women is “an expression of historically grown unequal power relations between women and men, which have led to the domination and discrimination of women by men and to the prevention of full equality of women” (Council of Europe 2011, p.3). Partner violence is therefore not an individual problem; it is not just about the relationship between two people, but also about the social environment.

The StoP concept offers a proven approach to build on this, to close the gap and bring about positive change.

StoP approach and essentials

Our basic principles include:

- the assumption that domestic violence is not a private matter, that it is underpinned by patriarchal traditions, social norms and structures, but that these can be changed.

- a positive view of humanity: people have compassion, care about others, reject injustice and are capable of taking action. When people join forces, they can learn from each other and have a greater impact together.

- the idea of networking, because protection and change require many players. StoP can only be successful in cooperation with e.g. civic associations, NGO, schools, local politicians, housing associations, counselling services and women's shelters.

- the research based belief that an informed, aware and supportive community makes a crucial difference in the spread of and response to patriarchal violence at home.

StoP uses the rich knowledge of community work and community organising to bring about sustainable change. Community organizing means: “A process of engaging whole communities – youth and adults; people of all genders; family, friends, and neighbors; professionals and politicians – in collectively articulating the problem, developing an expansive vision, building collective power and capacity, and creating both personal and social change.” (Aimee Thompson, close2home)

StoP Organising Process

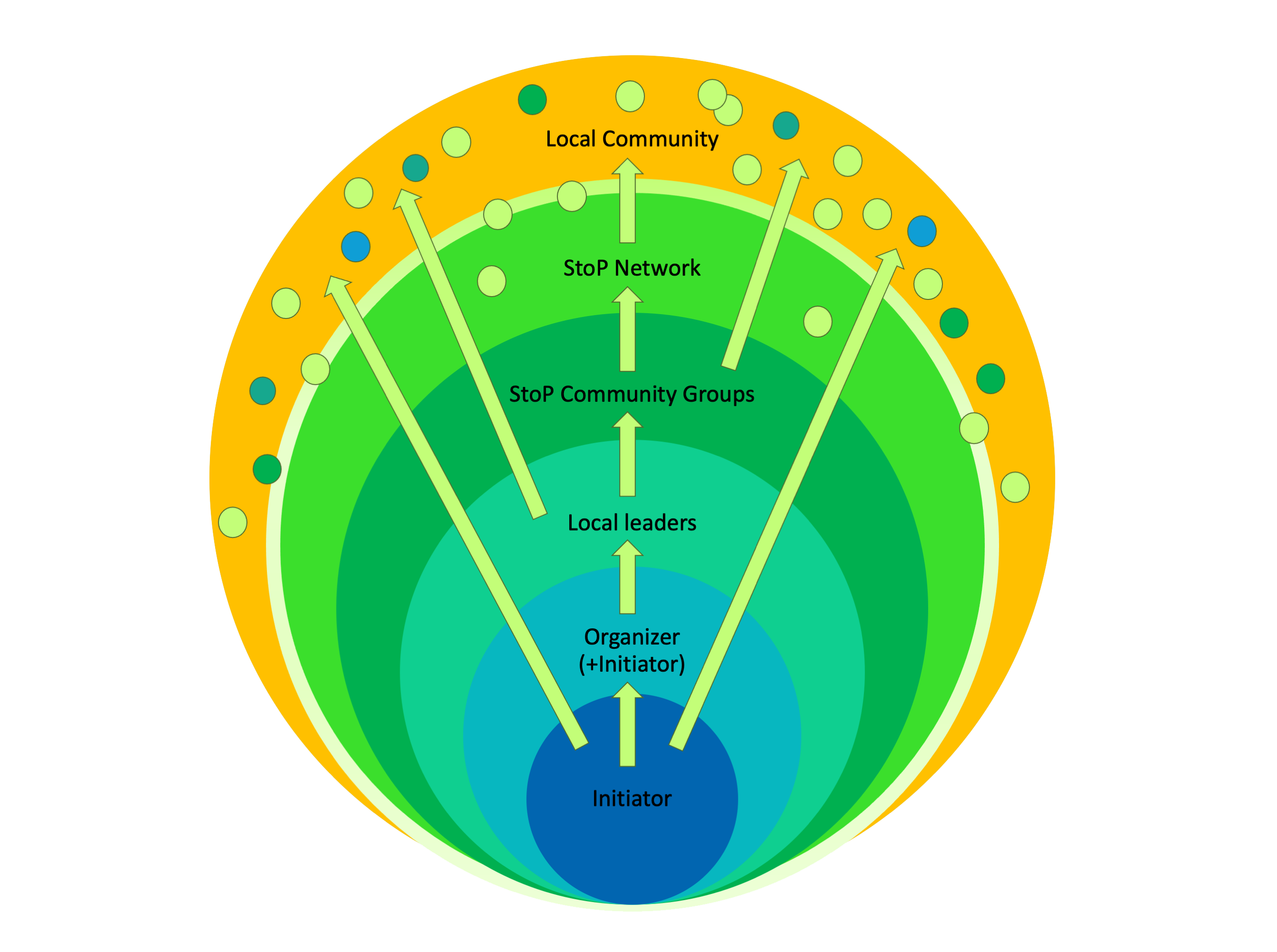

- Initiators mobilise resources and employ organisers who (some-times together with the initiators) carry out community assessments and find/mobilise local leaders through one-to-one meetings, who then (some of them) become part of the local StoP network and recommend, mobilise, connect organisers to other community members.

- with the help of the organiser, organise themselves and form the StoP community group(s) that are at the heart of the further organising process. Together they form the local StoP community network. Members of the local community can participate and support the network on special occasions. In addition organisers might also contact community members directly.

“My vision is all about non-violence all over the world, and that's what I'm aiming for. I'm talking about the 'grassroots movement', the ecological movement, the anti-nuclear power movement... all of that. And now it's time to say: StoP!”

The 8 Steps

1. Getting started

a firm commitment of a group or organisation to make StoP happen, by deciding to mobilise resources, to find and to provide trained community organisers, space and funding for the work.

2. Community assessment

the initial organisers systematically explore the community, identifying and talking to key people and local leaders.

3. Organising

engaging community members, building relationships and a consistent core group, raising awareness, defining a shared vision, developing skills and preparing for action.

4. Action

the group creates local campaigns and open public spaces to learn and talk about violence against women, the change the community wants and how to get there.

5. Networking

the issue of domestic violence is put on the agenda of community stakeholders and to establish cooperation at the district level.

6. Support

offering individual support to survivors and establishing links to the professional support system, such as counselling services, shelters.

7. Sustainability

ongoing, reliable small-scale relationship-building, organising and change work involving more people and institutions in the community.

8. Expansion

joining networks, build political alliances and support for our cause beyond the local community.

StoP Story

There are crucial experiences and encounters for many of us that inspire questions and the search for new solutions, as they create a crack in the daily routine and open a window for imagination. The starting point of StoP was when StoP’s founder Sabine Stövesand came to know Ayse while working in a womens’ shelter. Ayse’s story contains the vision that drives our work. It inspired a concrete utopia with more than 50 neighbourhoods in villages, small towns and cities in Germany and Austria implementing the StoP Model so far.

Ayses story

Ayse came to the shelter with her 5 kids. She was a working women from a poor part of town. She said she did not want to stay long, just wanted to get a break, recover from the assaults her husband inflicted on her and then go back to her apartment. In no way she wanted to leave the place to her husband, she wanted him out and reclaim it for herself and the kids. She said that she trusted in her neighbors to help her and that they are like family to her and the kids. She did not want herself and the kids to be the ones to lose everything – a home, friends, a social network, familiarity – on top of the violence.

So Ayse did as she said, although the husband kept on coming up to the door of her home and threatened her for quite a while. What gave her strength and motivation to overcome fear, to confront attacks and stalking was a supportive network of neighbors. She told me shedidn’t give up, got a divorce and stayed in her neighbourhood where she lived and raised her kids for many years.

This story inspired me to think about the benefits of community for the support and safety of victims. Later on I happened to work in the same neighbourhood where she lived and I reconstructed the whole story by finding and interviewing the local social worker who played a main part in bringing together Ayse’s support network after Ayse confided to her about her partner abusing her.

So what did the neighbors do?

They met regularly, discussed the situation and what to do. One of the outcomes was that people volunteered to enroll on a telephone list and formed a personal hotline for her. With Ayse’s consent they spread the word. One day a guy came up to the social worker, handed over a paper with the timetable of his working shifts and said: “My wife heard at the doctor’s waiting room that you need some help. You can put me on the list when I’m not working.”

Another measure was, that for about 6 months every day for a couple of hours, people would sit outside across the street of her home, to make it clear to the husband that he was watched and she was not alone.

One neighbour fixed her entrance door so it could not easily be broken and she could feel safer.

When things got too dangerous – the husband had a pistol and once shot through the windows – she went to the shelter where I met her. While she was there, the neighbors repaired the kitchen and bought a new carpet in her favourite colour. When she returned, they awaited her with a coffee table, cake and flowers.

So people in the community protected her, saved her from spending a lot of money and energy related to moving elsewhere, finding a new school and kindergarden, and she and the kids did not have to lose their friends and familiar setting.

Some of her community members despised her for the disclosure and divorce, but a significant group of neighbors from mixed ethnic and political backgrounds were supportive.

Also, her story had spin-off effects. The social worker later told me in an interview that in the course of these events, other people approached her, seeking help as victims of violence, as well as perpetrators. It is key that we assist both victims and perpetrators in order to break the cycle of violence.

The development and implementation of the StoP model is an ongoing process, triggered by questions and observations from the practice of women's shelter work, such as: women and their children have to make a costly escape to reach safety; there are too few shelters, many are overcrowded; victims informally confide in friends and acquaintances in their communities rather than going to official centres, but there is no investment in the prevention and protection potential of the community. This is why Sabine Stövesand left the shelter work and started as a community organizer.

- 1995: She founded the first neighbourhood group to combat violence against women in her district. They could gather experience, knowledge and particularly a lot of questions and concerns that formed the basis of a research project.

- 2002: A multi-year research project on the relevance and development of a community-based model of action started at Hamburg University of Applied (HAW) sciences led by Ms. Stövesand (dissertation)

- 2006: The results were published, the model was named StoP and subsequently presented in many cities and at conferences. International exchange with pioneers in the field such as Aimee Thompson (Close2home), Lori Michau (Raising Voices), Mimi Kim (Creative Interventions) and Cristy Trewartha (Heart Movement) also played an important role (see Metastudy 2022),

- 2010 to 2012: A StoP pilot project was implemented and scientifically monitored in the Hamburg district of Steilshoop with the support of the City of Hamburg and HAW. The Steilshoop project is still running today.

- Since 2013: The first series of training courses on the StoP concept started in Hamburg with 12 social workers and 5 neighbours involved in StoP Steilshoop. Since then, around 200 participants from Germany and Austria, as well as interested parties from the Czech Republic, Romania, Serbia, France and Belgium, have been trained to become StoP specialists as part of this EU Daphne 2024 project.

- Since 2014: 50 more StoP communites have since been added (with an upward trend), including in Austria from 2019. Thousands of people are involved in StoP neighbourhood groups, providing information through door-to-door canvassing, accompanying people to counselling centres, offering shelter and taking part in intervention training. At the annual bi-natinional gatherings 80 StoP delegates meet, learn from each other, bond , have fun and set new goals. StoP has become a movement.

StoP at a glance

Coming soon.

References

-

Browning, C. (2002). The span of collective efficacy: Extending social disorganization theory to partner violence. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(4), 833–850.

-

Bundeskriminalamt. (2023). Bundeslagebild häusliche Gewalt 2022. Wiesbaden: Bundeskriminalamt.

-

Bundesministerium des Innern und für Heimat. (2023). PKS 2022, ausgewählte Zahlen. Berlin. Retrieved from https://www.bka.de/DE/AktuelleInformationen/StatistikenLagebilder/PolizeilicheKriminalstatistik/PKS2022/FachlicheBroschueren/fachlicheBroschueren_node.html

-

Council of Europe. (2011). Übereinkommen des Europarats zur Verhütung und Bekämpfung von Gewalt gegen Frauen und häuslicher Gewalt (Council of Europe Treaty Series—No 210). Istanbul. Retrieved from https://rm.coe.int/1680462535

-

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA). (2014). Gewalt gegen Frauen: Eine EU-weite Erhebung. Ergebnisse auf einen Blick. Retrieved from http://fra.europa.eu/de/publication/2014/gewalt-gegen-frauen-eine-eu-weite-erhebung-ergebnisse-auf-einen-blick

-

Gloor, D., & Meier, H. (2022). Community matters: A metastudy on the prevention of violence against women and domestic violence. Study commissioned by Hamburg University of Applied Sciences. Retrieved from https://stop-partnergewalt.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Study_Community_GbV_EN.pdf

-

Šimonović, D. (2019). Ending violence against women and girls: Progress and remaining challenges. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/en/un-chronicle/ending-violence-against-women-and-girls-progress-and-remaining-challenges

-

UN Women. (2019). Violence against women. Retrieved from https://interactive.unwomen.org/multimedia/infographic/violenceagainstwomen/en/index.html#home

Bienvenue chez StoP! Voici quelques informations sur StoP. Avec cette approche d’un travail social communautaire au niveau des quartiers, nous sommes une voix engagée dans la lutte contre la violence masculine quotidienne et omniprésente. Nous nous concentrons sur les violences conjugales qui touchent surtout les femmes, partout dans le monde. Notre but: un changement social venant des citoyen·nes, et des relations de couple égalitaires et fondées sur l'amour, le tout par la mobilisation, l'empathie et le soutien de la société civile et des communautés locales.

La mission de StoP

Le concept de StoP vient d'Allemagne; StoP est une abréviation de «Stadtteile ohne Partnergewalt» (en français: quartiers sans violence conjugale). Ce nom exprime notre mission principale: prévenir et mettre un terme à la violence dans les relations entre (ex-) partenaires intimes, violence qu'on appelle souvent violence conjugale.

StoP cible la violence masculine envers les femmes, notamment l'abus de pouvoir et le contrôle à travers la violence physique, sexuelle, psychologique, économique et sociale.

Cette violence n’est pas isolée du reste de la vie quotidienne – les voisin·e·s, ami·e·s ou collègues suspectent, entendent ou voient quelque chose. Si certain·e·s. y sont indifférent·e·s, ne veulent pas s'en mêler ou encore trouvent normal de traiter les femmes ainsi, la plupart du temps, les gens veulent aider, mais ne savent pas comment. On doute, on a peur. C'est là que StoP intervient – nous mobilisons le potentiel de soutien et de changement de tout un quartier et renforçons ainsi la société civile.

Les recherches ont montré que les réactions de notre entourage ont un impact: elles peuvent sauver des vies, augmenter ou mettre fin à la violence. C'est pourquoi StoP veut outiller et autonomiser les communautés et les citoyen·ne·s au niveau local.

StoP améliore la sécurité et promeut des relations respectueuses, affectueuses et égalitaires. A cette fin, nous voulons 1) encourager les victimes et les agresseurs à rompre le silence et à chercher de l'aide, et 2) construire à la base même de la société la détermination et les compétences pour la mobilisation locale et le changement social.

Nous sommes convaincu·e·s que prévenir les violences conjugales et construire des rapports sociaux solidaires conduiront à réduire la violence en général. Sur le long terme, le travail de StoP peut contribuer à une société plus démocratique, dans une égalité totale, où personne ne souffrira de violence ou de discrimination.

The change StoP is about

Des voisin·e·s baissent le son de leur télé et écoutent les cris et coups qui viennent de l'appartement d'à côté. Pour interrompre la violence, elles sonnent à la porte de cet appartement et demandent s'iels peuvent emprunter un chargeur de téléphone. Ils appellent la police. Iels mettent en place une chaîne téléphonique pour soutenir la femme victime. Elles lui proposent de l'héberger. Quelqu'un l'aide à renforcer la porte d'entrée contre «les cambrioleurs». Ils vont à la rencontre d'autres voisin·e·s au centre commercial pour les informer sur les violences conjugales. La crèche les invite pour parler de ce sujet lors de la soirée des parents. Les concierges distribuent des flyers de StoP dans les boîtes aux lettres, laissent les autocollants StoP collés sur la porte d'entrée et mettent des affiches StoP sur les panneaux d'information réservés à la société de logement. L'école intègre le sujet de la violence conjugale dans son curriculum. La maison de quartier propose des ateliers d’affirmation de soi et de désescalade. Le groupe hip hop du club des jeunes crée un rap et les mots «loi de protection contre les violences» résonnent dans les baffles. Les femmes se réunissent et organisent le départ d'une voisine vers une maison d'accueil. Une femme de StoP organise des soirées Tupperware et avant chaque réunion, elle parle du sujet, distribue des dépliants et fait connaître StoP. L'épicier a mis une affiche StoP avec le numéro de la ligne d'écoute dans sa vitrine. Chez le coiffeur, au café et au cabinet médical, partout il y a des affiches. Tous les commerces et associations locaux signent une déclaration que la violence conjugale n'est pas une affaire privée et ne sera pas tolérée. La pub sexiste n'a pas sa place dans le quartier: en deux temps trois mouvements, quelqu'un l'a arrachée, dessiné dessus...Les femmes ne rasent plus les murs de la cage d'escalier avec des lunettes de soleil pour cacher leurs bleus, mais sonnent chez les voisin·e·s et demandent des conseils. Les voisin·e·s trans et queer se sentent plus en sécurité. Ils et elles savent qu'iels trouveront de la compréhension et du soutien et non de l'indifférence ou des commentaires sexistes. La violence conjugale devient un sujet public. Les réseaux sociaux locaux deviennent une ressource d'autonomisation et de changement social durable.

Pourquoi StoP

Depuis le mouvement des femmes des années 1970, nous avons fait beaucoup de progrès pour lutter contre les violences faites aux femmes et soutenir celles qui en souffrent. Mais ce n'est pas assez. Pourquoi?

- Comme le dit la rapporteuse UN Dubravka Šimonović: «Récemment nous avons vu, à la fois au niveau régional et international, une sensibilité accrue pour les droits des femmes, mais aussi la persistance des violences faites aux femmes et aux filles dans toutes les couches de la société.» (2019, n.p.) La prévalence de la violence reste élevée. Les violences faites aux femmes sont la forme la plus fréquente de violations des droits humains: «Que ce soit à la maison, dans la rue ou pendant la guerre, les violences faites aux femmes et aux filles sont une violation des droits humains à échelle pandémique qui a lieu dans les espaces public et privé.» (UN Women 2019, n.p.). En Allemagne par exemple, une femme est tuée par son (ex-)partenaire tous les trois jours et une tentative de meurtre a lieu chaque jour. Et c'est seulement la pointe émergée de l'iceberg (BKA 2023: 14, IMK 2023: 9). La situation est similaire dans d'autres pays.

- L'écart: Certains quartiers manquent de lieux dédiés, et quand il y en a, les obstacles pour y accéder sont souvent nombreux. Le manque d'information, la peur, la honte, la méfiance et la pauvreté empêchent les victimes de chercher de l'aide. Par exemple, 67% des femmes victimes n'ont pas parlé de la violence la plus grave qu'elles ont vécue, ni à la police, ni à d'autres organismes (FRA 2014).

- La plupart des solutions ne sont mises en place qu’après les épisodes de violence. Le contexte spécifique de ces actes et le potentiel des voisin·e·s, ami·e·s et communautés sont négligés. Or, des études montrent que les normes de l'entourage et la qualité du contexte social local réduisent la violence conjugale, diminuent le taux de féminicides et promeuvent des relations égalitaires. Quand l'efficacité collective d'un quartier est forte et que les femmes sont bien entourées, elles parlent plus facilement de la violence vécue et cherchent de l'aide (Browning 2002, Metastudy 2022).Les voisin·e·s ont l'avantage d’être géographiquement proches. En cas de crise, elles et ils sont facilement joignables. Impliqué·e·s directement ou indirectement (entendre, voir, suspecter...), ils et elles peuvent aider à prévenir l'escalade et à stopper la violence, proposer un soutien au quotidien, informer sur les aides disponibles.

- La Convention d'Istanbul prévoit ce type de programme, car elle souligne l'importance de la prévention et de la société civile et constate que les violences faites aux femmes sont «une manifestation des rapports de force historiquement inégaux entre les femmes et les hommes ayant conduit à la domination et à la discrimination des femmes par les hommes, privant ainsi les femmes de leur pleine émancipation» (Conseil de l'Europe 2011, p. 2). La violence conjugale n'est donc pas un problème individuel ; il ne s'agit pas uniquement d'une relation entre deux personnes, mais aussi de leur environnement social. Le concept StoP propose une approche avérée pour fermer l'écart et engendrer un changement positif.

L'approche StoP et ses éléments clés

Nos principes fondamentaux incluent:

- la compréhension que la violence conjugale n'est pas une affaire privée, qu'elle se fonde sur des traditions patriarcales, des normes et des structures sociales, et que celles-ci peuvent être modifiées.

- une vision positive de l'humanité: les gens sont empathiques, se soucient des autres, rejettent l'injustice et sont capables d'agir. Lorsque les gens unissent leurs forces, ils peuvent apprendre les uns des autres et avoir un plus grand impact.

- le travail en réseau, car la protection et le changement nécessitent de nombreux·euses acteurs·rices. StoP ne peut réussir qu'en coopération avec, par exemple, des associations, des écoles, des élu·e·s locales·aux, des organismes de logement et des structures d'accueil pour femmes.

- la conviction, fondée sur la recherche, qu'une communauté locale informée, conscientisée et solidaire fait une différence cruciale dans la prévention de la violence patriarcale et dans la réponse à y apporter.

StoP utilise les formidables apports du travail social de terrain pour apporter un changement durable: «Un processus d'engagement de quartiers entiers – jeunes et adultes, personnes de tous genres, familles, ami·e·s et voisin·e·s, professionnel·le·s et élu·e·s – dans la formulation collective du problème, le développement d'une vision élargie, la construction de capacités et de pouvoir collectifs, et la création d'un changement à la fois personnel et social.» (Aimee Thompson, close2home)

Le processus StoP consiste en 8 étapes

- Démarrer: un groupe ou une organisation s'engage fermement à mettre StoP en pratique, en mobilisant des ressources, à savoir en recrutant des coordinateurs·rices StoP formé·e·s et en trouvant un espace et un financement.

- Analyser la communauté locale: les partenaires initiaux·ales explorent systématiquement les possibilités dans la communauté, identifient les personnes clés et les leaders locales·aux et s'entretiennent avec eux et elles.

- Mobiliser: les coordinatrices·eurs StoP impliquent les membres de la communauté locale, établissent des relations et un noyau dur cohérent, sensibilisent, définissent une vision commune, développent des compétences et préparent l'action.

- Agir: le groupe crée des campagnes locales et ouvre des espaces publics pour parler de la violence conjugale, du changement souhaité par la collectivité et de la manière d'y parvenir.

- Réseauter: la question de la violence conjugale est inscrite à l'ordre du jour des organisations locales et permet d'établir une coopération au niveau de l'arrondissement.

- Soutenir: les coordinateurs·rices StoP offrent un soutien individuel aux victimes et établissent des liens avec les services de soutien professionnels, c’est-à-dire les structures d'accueil et de consultation.

- Pérenniser: Les partenaires travaillent de manière continue et fiable pour établir des relations, mobiliser et effectuer un changement à petite échelle, en impliquant davantage de personnes et d'organisations dans le quartier.

- Elargir: Le projet StoP rejoint des réseaux, construit des alliances politiques et soutient notre cause au-delà de la communauté locale.

Un témoignage StoP

Pour beaucoup d'entre nous, des expériences et des rencontres importantes amènent des questions et la recherche de nouvelles solutions, peut-être parce qu'elles nous détournent de la routine quotidienne et ouvrent une fenêtre sur l'imagination. Lorsque la fondatrice de StoP, Sabine Stövesand, a fait la connaissance d'Ayse alors qu'elle travaillait dans une maison d'hébergement pour femmes victimes de violence conjugale, ce fut le point de départ de StoP. L'histoire d'Ayse contient la vision qui motive notre travail. Elle a inspiré une utopie concrète: à ce jour, plus de 50 quartiers de villages, de petites et de grandes villes allemandes et autrichiennes ont mis en œuvre le concept StoP. Le développement et la mise en œuvre du modèle StoP est un processus continu, déclenché par des questions et des observations issues de la pratique des maisons d'accueil et d’hébergement pour femmes victimes de violence conjugale, telles que: les femmes et leurs enfants doivent s'enfuir à grands frais pour se mettre en sécurité ; il y a trop peu de places, beaucoup de structures sont surpeuplées ; les victimes se confient de manière informelle à des ami·e·s et à des connaissances plutôt que de se rendre dans des services spécialisés, mais il n'y a pas d'investissement dans le potentiel de prévention et de protection de la communauté locale. Voyant cela, Sabine Stövesand a quitté son emploi dans les maisons d'accueil et s'est lancée dans le travail social au niveau local.

1995: Mme Stövesand fonde le premier groupe de voisin·e·s pour lutter contre la violence conjugale dans son quartier. Les membres du groupe y acquièrent de l'expérience et des connaissances, et formulent de nombreuses questions qui servent de base à un projet de recherche.

2002: Un projet de recherche pluriannuel sur la pertinence et le développement d'un modèle d'action communautaire est lancé à l'Université des sciences appliquées de Hambourg (HAW) sous la direction de Mme Stövesand (thèse).

2006: Les résultats sont publiés, le modèle est baptisé StoP et est ensuite présenté dans de nombreuses villes et lors de conférences. Les échanges internationaux avec des pionnières du domaine tels que Aimee Thompson (Close2home), Lori Michau (Raising Voices), Mimi Kim (Creative Interventions) et Cristy Trewartha (Heart Movement) ont également joué un rôle important (voir méta-étude 2022).

2010 à 2012: Un projet pilote StoP est mis en œuvre avec un suivi scientifique dans le quartier de Steilshoop, soutenu par la Ville de Hambourg et la HAW. Le projet Steilshoop est toujours en cours aujourd'hui.

Depuis 2013: La première série de formations de coordinatrices·eurs StoP débute à Hambourg avec 12 travailleuses·eurs sociales·aux et 5 voisin·e·s impliqué·e·s dans StoP Steilshoop. Depuis lors, environ 200 participant·e·s d'Allemagne et d'Autriche, ainsi que de République tchèque, de Roumanie, de Serbie, de France et de Belgique dans le cadre du présent projet Daphne de l'UE, ont été formé·e·s pour devenir des coordinateurs·rices StoP.

Depuis 2019: 50 communautés StoP supplémentaires (avec une tendance à la hausse). Des milliers de personnes sont impliquées dans les groupes de quartier StoP, fournissant des informations par le biais du porte-à-porte, accompagnant les personnes vers les services d'aide, offrant un abri et participant à la formation à l'intervention par les témoins. Lors des rassemblements annuels binationaux, 80 délégué·e·s StoP se rencontrent, apprennent les un·e·s des autres, tissent des liens, s'amusent et se fixent de nouveaux objectifs. StoP est devenu un mouvement.

L'histoire de Ayse

Ayse arriva dans la maison d'hébergement avec ses cinq enfants. Elle était ouvrière et habitait dans un quartier défavorisé de la ville. Elle dit qu'elle ne pouvait pas rester longtemps, qu'elle avait juste besoin d'une pause pour se remettre des agressions que son mari lui avait infligées, et qu’ensuite elle allait retourner dans son appartement. En aucun cas, le mari ne devait récupérer l'appartement, elle voulait qu'il s'en aille et qu'elle le reprenne pour elle et ses enfants. Elle expliqua qu'elle faisait confiance à ses voisin·e·s pour l'aider et qu'ils étaient comme une famille pour elle et ses enfants. Elle ne voulait pas que ce soit elle et les enfants qui perdent tout – une maison, des ami·e·s, un réseau social, des lieux familiers – en plus de subir la violence.

Ayse fit donc ce qu'elle a dit, bien que le mari ait continué à venir devant sa maison et à la menacer pendant un certain temps. Ce qui lui a donné la force et la motivation de surmonter la peur, de faire face aux attaques et au harcèlement, c'était tout un réseau de voisin·e·s qui la soutenaient, comme elle me l'a dit. Elle n'a pas abandonné, a divorcé et est restée dans le quartier où elle vivait et élevait ses enfants depuis de nombreuses années.

Cette histoire m'a incitée à réfléchir aux avantages qu'a la communauté locale pour soutenir et protéger des victimes. Plus tard, j'ai travaillé dans le quartier où elle vivait et j'ai reconstitué toute l'histoire en retrouvant et en interrogeant l'assistante sociale locale qui a joué un rôle essentiel dans la mise en place du réseau de soutien d'Ayse, après qu'Ayse lui a confié que son conjoint était violent.

Qu'ont donc fait ses voisin·e·s ?

Ils et elles se sont réuni·e·s régulièrement, ont discuté de la situation et de ce qu'il fallait faire. L'un des résultats a été que des personnes se sont inscrites sur une liste téléphonique pour former une ligne d'assistance personnelle pour Ayse. Avec l'accord d'Ayse, ils ont fait passer le mot. Un jour, un homme s'est approché de l'assistante sociale, lui a tendu un papier avec ses horaires de travail et lui a dit: « Ma femme a entendu dire dans la salle d'attente du médecin que vous aviez besoin d'aide. Vous pouvez m'inscrire sur la liste lorsque je ne travaille pas.»

Une autre mesure a consisté à ce que, pendant environ six mois, des voisins se sont assis chaque jour plusieurs heures de l'autre côté de la rue, pour faire comprendre au mari qu'il était surveillé et qu'elle n'était pas seule.

Une voisine a fait renforcer sa porte d'entrée pour qu'elle se sente plus en sécurité.

Lorsque la situation devenait trop dangereuse – le mari avait un pistolet et avait déjà tiré à travers les fenêtres – elle s'est rendue à la maison d'accueil où je l'ai rencontrée. Pendant son séjour, les voisin·e·s ont rénové sa cuisine et lui ont acheté un nouveau tapis de sa couleur préférée. Lorsqu'elle est revenue, tout le monde l’attendait avec une table basse, des gâteaux et des fleurs.

Ainsi, les membres de la communauté locale l'ont protégée, lui ont évité de dépenser beaucoup d'argent et d'énergie pour déménager, trouver une nouvelle école et une crèche, et elle et ses enfants n'ont pas dû abandonner leurs ami·e·s et leur environnement familier.

Certains membres de sa communauté l'ont méprisée pour le fait qu'elle a parlé de la violence et qu'elle a divorcé, mais un groupe plus important de voisin·e·s d'origines et convictions diverses l'ont soutenue.

Son histoire a également eu des retombées. L'assistante sociale m'a dit plus tard, lors d'un entretien, qu'au cours de ces événements, d'autres personnes l'avaient approchée pour lui demander de l'aide – des victimes comme des agresseurs.

StoP en un coup d'œil

Vítejte na stránkách StoP! Jsme komunitní projekt, který bojuje proti domácímu násilí a násilí na ženách. Naším cílem je dosáhnout sociálních změn a podporovat rovnocenné a zdravé vztahy prostřednictvím mobilizace a podpory místních komunit.

Mise StoP

Koncept projektu StoP pochází z Německa a písmena znamenají zkratku “Stadtteile ohne Partnergewalt” („Místní komunity bez partnerského násilí“). Naším hlavním posláním je zastavit a předcházet násilí v partnerských vztazích.

StoP se zaměřuje na problematiku domácího násilí a násilí páchaného na ženách. Toto násilí často zahrnuje fyzické, sexuální, psychologické, ekonomické a sociální útoky, které slouží k uplatňování moci a kontroly v blízkých vztazích.

Toto násilí se neděje izolovaně; sousedé, přátelé nebo kolegové si mohou něčeho všimnout, slyšet nebo vidět. Někteří vůči tomu mohou být lhostejní, myslet si, že se jich to netýká, nebo že je takové chování vůči ženám normální. Většina z nich však chce pomoci, ale nevědí jak, cítí se nejistě nebo se bojí. A právě zde je prostor pro projekt StoP – mobilizujeme podporu a potenciál změny v sousedství a občanské společnosti.

Studie ukazují, že postoje a činy lidí kolem nás mají velký význam a mohou zachránit životy nebo zastavit násilí. Proto se StoP snaží vzdělávat a posílit jednotlivce a místní komunity. Ty mohou hrát klíčovou roli v tom, aby násilí v blízkých vztazích nebylo tolerováno nebo ignorováno.

StoP se podílí na zvyšování bezpečí a podporuje respektující, láskyplné a rovnocenné vztahy. Abychom toho dosáhli, snažíme se:

Zvýšit ochotu obětí a pachatelů prolomit mlčení a vyhledat pomoc.

Systematicky budovat motivaci a dovednosti pro mobilizaci komunity a sociální změnu na místní úrovni.

Věříme, že prevence domácího násilí a budování podpůrných sociálních vztahů povede ke snížení násilí obecně. V dlouhodobém horizontu může práce StoP přispět k demokratičtější společnosti, kde není místo pro násilí a diskriminaci.

Jaká je naše vize a jak by vypadal svět, kdyby byl aplikován program StoP?

Pokud by sousedé slyšeli křik a bouchání z vedlejšího bytu, ztlumí televizi a zazvoní s výmluvou, že si potřebují půjčit nabíječku, čímž násilí přeruší. Zavolají policii. Podpoří ženu zažívající násilí a nabídnou jí útočiště. Někdo pomůže zabezpečit její vchodové dveře. Setkají se s dalšími sousedy a informují je o domácím násilí, ke kterému dochází. V obytných domech jsou k dispozici informační letáky StoP a umožňují nalepit samolepky StoP na dveře a poštovní schránky, na informačních tabulích sdružení vlastníků nebo nájemníků jsou dostupné informace o pomoci pro oběti domácího násilí. Škola začleňuje téma partnerského násilí do výuky. Komunitní centrum nabízí kurzy sebeobrany a deeskalace násilí. Muži se setkávají a mluví o násilí a co dělat, aby mu předešli. Ženy se spojí, vytvoří skupinu a pomohou sousedce utéct do azylového domu. Žena ze skupiny StoP pořádá sousedská setkání, kde hovoří o tomto tématu, rozdává letáky a propaguje StoP. Plakát StoP s kontakty na azylové domy a poradny visí ve výloze zelinářství, v kadeřnictví, hospodě i ordinaci lékaře. Místní podniky a asociace se společně zaváží, že partnerské násilí není soukromá věc a nebudou ho tolerovat. Sexistické reklamy v okolí nemají šanci, jsou přelepeny nebo přemalovány. Ženy už se ze studu nemusí skrývat za sluneční brýle, ale mohou zazvonit na dveře sousedů a požádat o radu. Domácí násilí se stává veřejným tématem. Místní sociální sítě se stávají zdrojem posílení a trvalé sociální změny.

Proč potřebujeme programy jako je StoP?

Od dob ženského hnutí v 70. letech bylo učiněno mnoho pro potírání násilí na ženách a domácího násilí a pro podporu těch, které násilí zažívají.

To ale nestačí! Proč?

- Slovy zpravodajky OSN Dubravky Šimonović: (2019, n.p.): “V poslední době jsme na regionální i mezinárodní úrovni svědky zvyšování povědomí o právech žen, ale také přetrvávajícího genderově podmíněného násilí na ženách a dívkách napříč všemi vrstvami společnosti”. Výskyt násilí je stále vysoký. Násilí na ženách je nejčastějším porušováním lidských práv: “Ať už doma, na ulici nebo během války, násilí na ženách a dívkách je porušováním lidských práv pandemických rozměrů, které se odehrává na veřejnosti a v prostoru” (UN Women 2019, n.p.). Například v Německu je téměř každý třetí den zabita žena svým (bývalým) partnerem a každý den dojde k pokusu o vraždu. A to je jen špička ledovce (BKA 2023: 14, IMK 2023: 9). V České republice je v důsledku domácího násilí každoročně zabito několik desítek žen a dětí. Podobná situace je i v dalších zemích.

- Nedostatečná podpora: Dostupnost specializované pomoci není dostatečná (viz Analýza dostupnosti specializovaných služeb pro oběti domácího a genderově podmíněného násilí, MPSV). Vyhledání pomoci je často obtížné také kvůli nedostatku informací, strachu, studu, nedůvěře a chudobě. Podle studie Agentury EU pro lidská práva oznámí na policii nejzávažnější incident fyzického násilí pouze 8% obětí (FRA, 2014).

- Pozdní intervence: Většina intervencí nastává až poté, kdy k násilí dojde. Preventivní potenciál pomoci od sousedů, přátel a komunity není využit. Studie ukazují, že silná komunita a dobré místní vztahy snižují domácí násilí, vraždy žen a podporují rovnost v partnerských vztazích. V místech, kde jsou komunity silné a ženy mají více přátel, se častěji svěří a vyhledají pomoc. (Browning 2002, Metastudie 2022). Sousedé jsou vždy nablízku a v krizové situaci je snadné je kontaktovat. Často jsou zapojeni (slyší, vidí, tuší) a někdy se cítí přímo ovlivněni (hněv, strach, obavy, empatie). Mohou zabránit eskalaci a zastavit násilí! Můžou nabídnout podporu a poskytnout informace o dostupné pomoci.

- Partnerské násilí není problémem jednotlivce, netýká se pouze vztahu mezi dvěma lidmi, ale také sociálního prostředí.

Přístup a východiska projektu StoP

Základní východiska:

- Domácí násilí není soukromou záležitostí, často ho umožňují a legitimizují předsudky, tradice a společenské normy, které lze změnit.

- Lidé mají soucit a starají se o druhé. Spojením sil mohou dosáhnout větších změn.

- Úspěch programů StoP závisí na spolupráci s občanskými sdruženími, nevládními organizacemi, školami, místními politiky a dalšími.

- Informovaná a podporující komunita má zásadní vliv na snížení domácího násilí.

StoP využívá bohaté znalosti komunitní práce a komunitního organizování k dosažení udržitelných změn. Komunitní organizování znamená: “Proces zapojení celých komunit – mládeže i dospělých, rodiny, přátel a sousedů, odborníků i politiků – do kolektivního formulování problému, vytváření rozsáhlé vize, budování kolektivní moci a kapacity a vytváření osobní i společenské změny.” (Aimee Thompson, close2home)

Proces realizace programu StoP se skládá z 8 kroků:

- Začínáme: závazek skupiny obyvatel nebo organizace k realizaci StoP, mobilizace zdrojů, hledání komunitních organizátorů, zajištění prostor a finančních prostředků.

- Prozkoumání komunity: identifikace klíčových osob a formálních i neformálních lídrů, kterým komunitní organizátoři představují a vysvětlují záměry programu.

- Organizace: zapojení členů komunity, budování vztahů, zvyšování povědomí o domácím násilí a násilí na ženách, definování vize, rozvoj dovedností a příprava na aktivity.

- Aktivity: vytváření kampaní, otevírání veřejné diskuse o násilí na ženách a žádoucích změnách.

- Budování spolupráce a vytváření sítí: zahrnutí problematiky domácího násilí do agendy a spolupráce na úrovni komunity, obce či městské části.

- Podpora: nabídka podpory obětem a propojení se specializovanými službami pro podporu obětí domácího násilí, jako jsou specializované poradny, azylové domy, krizové linky a krizová centra.

- Udržitelnost: trvalé budování vztahů a organizace práce na změnách zahrnující více lidí a institucí.

- Expanze: zapojení do sítí, budování aliancí a podpora mimo místní komunitu.

Příběh projektu StoP

Pro mnohé z nás jsou zásadní zážitky a setkání, jež nás inspirují k otázkám a hledání nových řešení. Projekt StoP se začal rozvíjet, když zakladatelka projektu StoP Sabine Stövesandová poznala v azylovém domě pro oběti domácího násilí Aysu. Příběh Ayse se stal vizí, která je hnacím motorem naší práce. Od té doby se model StoP realizoval již ve více než 50 čtvrtích v Německu a Rakousku. Vývoj modelu StoP je pokračující proces, který byl ovlivněn zkušenostmi z praxe v azylových domech:

- Ženy a jejich děti musí nákladně utíkat, aby se dostaly do bezpečí.

- Azylových domů je málo a jsou přeplněné.

- Oběti se svěřují přátelům a známým spíše než oficiálním místům a centrům pomoci, ale prevence a ochranný potenciál komunity není využit.

Vývoj projektu

Proto Sabine Stövesandová opustila práci v azylových domech a začala pracovat jako komunitní organizátorka. 1995: Založení první sousedské skupiny proti násilí na ženách. Skupina shromáždila zkušenosti a poznatky pro výzkum.

2002: Zahájení víceletého výzkumného projektu na Vysoké škole aplikovaných věd v Hamburku (HAW) zaměřeného na rozvoj komunitního model pro aktivity směřující k prevenci domácího násilí.

2006: Zveřejnění výsledků, pojmenování modelu StoP a prezentace na konferencích. Důležitou roli sehrála také mezinárodní výměna zkušeností a informací s průkopníky v této oblasti, jako jsou Aimee Thompson (Close2home), Lori Michau (Raising Voices), Mimi Kim (Creative Interventions) a Cristy Trewartha (Heart Movement) (viz Metastudie 2022).

2010–2012: Pilotní projekt StoP v hamburské čtvrti Steilshoop s vědeckým monitorováním. Projekt Steilshoop probíhá dodnes.

Od 2013: První série školení o konceptu StoP v Hamburku, do které se zapojilo 12 sociálních pracovníků a 5 sousedů. Od té doby bylo vyškoleno přibližně 200 účastníků z Německa, Rakouska a také České republiky, Rumunska, Srbska, Francie a Belgie, kteří se stali odborníky na StoP.

Od 2014: V Německu a Rakousku (od roku 2019) přibylo dalších 50 obcí, které implementují program StoP. Sousedské skupiny StoP zapojují tisíce lidí do veřejných akcí, zvyšování povědomí, doprovázení lidí do poradenských center a intervenčních školení. StoP se stal hnutím, jehož součástí jsou každoroční setkání komunitních organizátorů a lidí zapojených do projektu.

Příběh Aysy

Ayse přišla do azylového domu se svými pěti dětmi. Byla to pracující žena z chudší části Hamburku. Nechtěla v azylovém domě zůstat dlouho; chtěla si jen odpočinout, vzpamatovat se z neustálých útoků manžela a vrátit se do svého bytu. Nechtěla nechat byt manželovi. Věřila, že jí sousedé pomohou a budou pro ni a její děti jako rodina. Nechtěla přijít o domov, přátele a sociální vazby.

Ayse nakonec udělala, co řekla, i když jí manžel stále vyhrožoval, chodil ke dveřím jejího bytu a vyhrožoval jí. To, co jí dodalo sílu a motivaci překonat strach, čelit útokům a pronásledování, byla podpora pomoc jejích sousedů. Nevzdala se, rozvedla se a zůstala ve svém domově, kde žila a vychovávala děti po mnoho let.

Příběh Aysi mě inspiroval k zamyšlení nad rolí komunity. Pracovala jsem ve stejné čtvrti, kde Aysa žila, a zjistila jsem, jak sousedé pomáhali.

Co udělali sousedé?

Pravidelně se scházeli, diskutovali o situaci a o tom, co dělat. Jedním z výsledků bylo, že se lidé dobrovolně zapsali do telefonního seznamu a vytvořili pro ni osobní linku důvěry. Se souhlasem Aysi ji šířili dál. Jednoho dne přišel za sociální pracovnicí muž, podal jí papír s rozpisem svých pracovních směn a řekl: “Moje žena se v čekárně u lékaře doslechla, že potřebujete pomoc. Můžete mě zapsat na seznam, když nepracuji.”

Dalším opatřením bylo, že asi půl roku každý den po několik hodin seděli lidé venku naproti jejímu domu, aby manželovi dali najevo, že je sledován a ona není sama.

Jedna sousedka jí opravila vchodové dveře, aby je nebylo možné snadno rozbít a ona se mohla cítit bezpečněji.

Když to začalo být příliš nebezpečné – manžel měl pistoli a jednou střílel do oken, přišla do azylového domu, kde jsem ji potkala. Zatímco tam byla, sousedé opravili kuchyň a koupili nový koberec v její oblíbené barvě. Když se vrátila, čekali na ni s prostřeným stolkem, dortem a květinami.

Lidé v komunitě ji tak ochránili, ušetřili jí spoustu peněz a energie spojených se stěhováním jinam, hledáním nové školy a školky a ona ani děti nemuseli přijít o své přátele a známé prostředí.

Někteří členové její komunity jí za toto odhalení a rozvod opovrhovali, ale významná skupina sousedů ze smíšeného etnického a politického prostředí ji podporovala.

Tento příběh měl i vedlejší účinky. Aysiina sociální pracovnice mi později v rozhovoru řekla, že v průběhu těchto událostí se na ni obrátili další lidé, kteří hledali pomoc, oběti násilí i pachatelé.

Bun-venit la StoP, vino și fă-ți o primă impresie despre ce este programul StoP. Prin munca noastră comunitară, bazată pe vecinătate, suntem o voce dedicată luptei împotriva violenței de gen prezentă în viața de zi cu zi. Ne concentrăm să prevenim violența domestică, care afectează în principal femeile din întreaga lume. Ce ne dorim să realizăm: schimbare socială și relații iubitoare, bazate pe egalitate, prin mobilizarea, empatia și sprijinul societății civile și al comunităților locale.

Misiunea StoP

Conceptul StoP provine din Germania, iar literele reprezintă „Stadtteile ohne Partnergewalt”. În română: „Comunități (locale) fără violență între parteneri”. Aceasta exprimă misiunea noastră principală: să oprim și să prevenim violența în relațiile intime, adesea denumită violență domestică. O formă comună a acestei violențe este exercitarea puterii și controlului în relațiile sociale apropiate, prin agresiuni fizice, sexuale, psihologice, economice și sociale.

Violența nu are loc într-un vid; vecinii, prietenii sau colegii bănuiesc, aud sau văd ceva. Ei pot fi indiferenți, pot considera că nu este treaba lor sau că este normal să tratezi femeile în acest fel. Însă, cel mai probabil, vor să ajute, dar nu știu cum, se simt nesiguri sau le este frică. Acesta este punctul de plecare al StoP - mobilizăm sprijinul și potențialul de schimbare al vecinătăților și societății civile.

Studiile arată că atitudinile și acțiunile oamenilor din jurul nostru fac o diferență: ele pot salva vieți, pot amplifica sau opri violența! De aceea, StoP își propune să educe și să împuternicească comunitățile la nivel local.

StoP îmbunătățește siguranța și promovează relații respectuoase, iubitoare și cu adevărat egale. Pentru a realiza acest lucru, ne propunem să: 1) creștem dorința victimelor și a agresorilor de a ieși în față, de a rupe tăcerea și de a căuta ajutor, și 2) să dezvoltăm sistematic voința și abilitățile pentru mobilizarea comunității și schimbarea socială la nivel de bază.

Credem că prevenirea violenței domestice și construirea unor relații sociale de sprijin vor reduce violența în general. Pe termen lung, munca StoP poate contribui la o societate mai democratică în care nimeni nu suferă violență sau discriminare.

Schimbarea pe care o aduce StoP:

Vecinii dau mai încet televizorul și ascultă țipetele și zgomotele care vin din apartamentul de lângă. Sună la ușa acestui apartament și întreabă dacă pot împrumuta un încărcător pentru telefonul mobil, întrerupând astfel violența. Sună la poliție. Îi oferă adăpost. Se întâlnesc cu alți vecini într-un centru comercial și îi informează despre violența domestică. Grădinița îi invită să discute despre acest subiect la întâlnirea cu părinții. Îngrijitorii distribuie pliante informaționale StoP și nu doar tolerează autocolantele StoP pe ușile de la intrare și pe căsuțele poștale, ci și afișează postere pe tabloul de anunțuri al asociației de locatari. Școala integrează subiectul violenței între parteneri în lecții. Femeile se adună, formează un grup și organizează evadarea unei vecine către un adăpost pentru femei. O femeie din grupul StoP organizează evenimente tematice și, de fiecare dată înainte de a începe, discută despre acest subiect, distribuie pliante și promovează StoP. Un poster StoP cu numerele adăposturilor pentru femei și ale centrelor de consiliere este expus în fereastra magazinului de legume-fructe. Și la frizerie, la pub și la cabinetul medicului. În plus, se face o declarație din partea tuturor afacerilor locale și a numeroaselor asociații din comunitate că violența între parteneri nu este o chestiune privată și nu va fi tolerată. Publicitatea sexistă nu are nicio șansă în comunitate; este acoperită, vopsită... în cel mai scurt timp. Violența domestică devine o problemă publică. Rețelele sociale locale devin o resursă pentru împuternicire și schimbare socială durabilă.

StoP rationale

De la mișcarea feministă din anii 1970, s-au făcut multe pentru a combate violența împotriva femeilor și pentru a sprijini persoanele afectate.

Dar: Nu este suficient! De ce?

- 1. În cuvintele raportorului ONU, Dubravka Šimonović: „Recent, atât la nivel regional, cât și internațional, am fost martorii unei conștientizări sporite a drepturilor femeilor, dar și a persistentei violențe de gen împotriva femeilor și fetelor din toate stratificările societății” (2019, n.p.). Prevalența violenței rămâne ridicată. Violența împotriva femeilor este cea mai frecventă încălcare a drepturilor omului: „Fie acasă, pe străzi sau în timpul războiului, violența împotriva femeilor și fetelor este o încălcare a drepturilor omului de proporții pandemice, care are loc în spații publice și private” (UN Women 2019, n.p.). În Germania, de exemplu, o femeie este ucisă de către partenerul său (fost sau actual) aproape la fiecare trei zile, iar o tentativă de omor are loc în fiecare zi. Și aceasta este doar vârful aisbergului (BKA 2023: 14, IMK 2023: 9). Situația este similară în alte țări.

- Decalajul: nu există suficient suport profesional disponibil, iar atunci când există, barierele pentru accesarea serviciilor specializate sunt adesea prea mari. Există o lipsă de informații, frică, rușine, neîncredere și sărăcie. De exemplu, 67% dintre victime nu au raportat cel mai grav incident de violență din partea partenerului la poliție sau la vreo altă organizație. (FRA 2014).

- Cele mai multe intervenții stabilite tind să fie eficiente doar după ce violența a avut loc. Contextul specific al crimei și potențialul vecinilor, prietenilor și comunităților sunt adesea neglijate. Totuși, studiile arată că normele comunității și calitatea contextului social local reduc violența în parteneriatele intime, scad rata femicidului și promovează egalitatea în relații. Acolo unde eficacitatea comunității este puternică și femeile au mai mulți prieteni, ele sunt mai predispuse să dezvăluie și să ceară ajutor (Browning 2002, Metastudy 2022). Vecinii au avantajul distanțelor scurte. Ei pot fi contactați rapid în situații de criză. De obicei, sunt implicați direct sau indirect (auzit, văzut, bănuind...) și uneori se simt afectați direct (furie, frică, iritare, îngrijorare, empatie). Ei pot ajuta la prevenirea escaladării și la oprirea violenței! Pot oferi sprijin în viața de zi cu zi și informații despre ceea ce este disponibil.

- Convenția de la Istanbul solicită un astfel de demers, subliniind importanța prevenirii și a societății civile, și afirmă că violența împotriva femeilor este „o expresie a relațiilor de putere inegale, care s-au dezvoltat istoric între femei și bărbați, ceea ce a condus la dominarea și discriminarea femeilor de către bărbați și la împiedicarea egalității complete a femeilor” (Consiliul Europei 2011, p. 3). Prin urmare, violența în parteneriate nu este o problemă individuală; nu este vorba doar despre relația dintre două persoane, ci și despre mediul social. Conceptul StoP oferă o abordare dovedită pe care se poate construi, poate închide această lacună și poate aduce schimbări pozitive.

Abordarea StoP și elementele esențiale

Principiile noastre de bază include:

- presupunerea că violența domestică nu este o chestiune privată, ci că este susținută de tradiții patriarhale, norme sociale și structuri, dar că acestea pot fi schimbate.

- o viziune pozitivă asupra umanității: oamenii au compasiune, le pasă de ceilalți, resping nedreptatea și sunt capabili să acționeze. Când oamenii colaborează, pot învăța unii de la alții și pot avea un impact mai mare împreună.

- ideea de rețea, deoarece protecția și schimbarea necesită mulți actori. StoP poate fi de succes doar în cooperare cu, de exemplu, asociații civice, ONG-uri, școli, politicieni locali, asociații de locuințe, servicii de consiliere și adăposturi pentru femei.

- credința bazată pe cercetare că o comunitate informată, conștientă și solidară face o diferență esențială în răspândirea și reacția la violența patriarhală în cadrul familiei.

StoP folosește cunoștințele bogate din domeniul muncii comunitare și organizării comunitare pentru a aduce schimbări durabile. Organizarea comunitară înseamnă: „Un proces de implicare a întregii comunități — tineri și adulți; persoane de toate genurile; familie, prieteni și vecini; profesioniști și politicieni — în articularea colectivă a problemei, dezvoltarea unei viziuni extinse, construirea puterii și capacității colective și crearea atât a schimbărilor personale, cât și a celor sociale. “ (Aimee Thompson, close2home)

Procesul StoP constă în 8 pași

- Începerea: un angajament ferm al unui grup sau organizații de a implementa StoP, prin decizia de a mobiliza resurse, de a găsi și a oferi organizatori comunitari instruiți, spațiu și finanțare pentru activitate.

- Evaluarea comunității: rganizatorii inițiali explorează sistematic comunitatea, identificând și discutând cu persoane cheie și lideri local.

- Organizarea: implicarea membrilor comunității, construirea relațiilor și a unui grup de bază consistent, creșterea conștientizării, definirea unei viziuni comune, dezvoltarea abilităților și pregătirea pentru acțiune.

- Acțiunea: grupul creează campanii locale și deschide spații publice pentru a învăța și a discuta despre violența împotriva femeilor, schimbarea dorită de comunitate și modul de a ajunge acolo.

- Rețea: problema violenței domestice este inclusă pe agenda părților interesate din comunitate și se stabilește cooperarea la nivel de cartier.

- Sprijin: oferirea de sprijin individual supraviețuitorilor și stabilirea de legături cu sistemul de sprijin profesional, cum ar fi serviciile de consiliere și adăposturile.

- Sustenabilitatea: construirea continuă și fiabilă a relațiilor la scară mică, organizarea și activitatea de schimbare implicând mai multe persoane și instituții din comunitate.

- Extindere: aderarea la rețele, construirea de alianțe politice și sprijin pentru cauza noastră dincolo de comunitatea locală.

Povestea StoP

Există experiențe și întâlniri cruciale pentru mulți dintre noi, care inspiră întrebări și căutarea de soluții noi, poate pentru că ele creează o fisură în rutina zilnică și deschid o fereastră pentru imaginație. Când fondatoarea StoP, Sabine Stövesand, a cunoscut-o pe Ayse în timp ce lucra într-un adăpost pentru femei, acesta a fost punctul de plecare al StoP. Povestea Ayses conține viziunea care ne ghidează munca. Aceasta a inspirat o utopie concretă, cu peste 50 de cartiere în sate, orașe mici și mari din Germania și Austria, care Dezvoltarea și implementarea modelului StoP este un proces continuu, generat de întrebări și observații din practica muncii în adăposturile pentru femei, cum ar fi: femeile și copiii lor trebuie să facă o evadare costisitoare pentru a ajunge în siguranță; există prea puține adăposturi, multe fiind suprapopulate; victimele se destăinuie informal prietenilor și cunoștințelor din comunitățile lor în loc să meargă la centrele oficiale, dar nu există investiții în potențialul de prevenire și protecție al comunității. De aceea, Sabine Stövesand a părăsit munca în adăposturi și a început să lucreze ca organizator comunitar.

1995: ea a fondat primul grup de cartier pentru combaterea violenței împotriva femeilor în districtul ei. A putut acumula experiență, cunoștințe și, în special, o mulțime de întrebări și preocupări care au constituit baza unui proiect de cercetare.

2002: un proiect de cercetare pe mai mulți ani privind relevanța și dezvoltarea unui model de acțiune bazat pe comunitate a început la Universitatea de Științe Aplicate din Hamburg (HAW), condus de doamna Stövesand (disertație)

2006: rezultatele au fost publicate, modelul a fost numit StoP și ulterior a fost prezentat în multe orașe și la conferințe. Schimbul internațional cu pionieri din domeniu, cum ar fi Aimee Thompson (Close2home), Lori Michau (Raising Voices), Mimi Kim (Creative Interventions) și Cristy Trewartha (Heart Movement), a jucat de asemenea un rol important (vezi Metastudiul 2022).

2010 până în 2012: un proiect pilot StoP a fost implementat și monitorizat științific în districtul Steilshoop din Hamburg, cu sprijinul orașului Hamburg și al HAW. Proiectul Steilshoop este în continuare activ și astăzi.

Din 2013: prima serie de cursuri de formare pe conceptul StoP a început în Hamburg cu 12 lucrători sociali și 5 vecini implicați în StoP Steilshoop. De atunci, aproximativ 200 de participanți din Germania și Austria, precum și persoane interesate din Republica Cehă, România, Serbia, Franța și Belgia, au fost instruiți pentru a deveni specialiști StoP ca parte a acestui proiect EU Daphne 2024.

Din 2014: încă 50 de comunități StoP s-au adăugat de atunci (cu o tendință în creștere), inclusiv în Austria din 2019. Mii de oameni sunt implicați în grupurile de cartier StoP, oferind informații prin campanii de informare la ușa, însoțind persoane la centrele de consiliere, oferind adăpost și participând la traininguri de intervenție. La întâlnirile anuale bilaterale, 80 de delegați StoP se întâlnesc, învață unii de la alții, se conectează și se distrează, stabilind noi obiective. StoP a devenit o mișcare.implementează deja Modelul StoP.

Ayse a venit la adăpost cu cei 5 copii ai săi. Era o femeie muncitoare dintr-o zonă săracă a orașului. A spus că nu vrea să rămână mult timp, ci doar să aibă o pauză, să se recupereze după atacurile pe care soțul ei i le-a provocat și apoi să se întoarcă la apartamentul ei. În niciun caz nu voia să-l lase pe soțul ei să rămână acolo; voia să-l scoată afară și să-și recâștige locuința pentru ea și copii. A spus că are încredere în vecinii ei să o ajute și că aceștia sunt ca o familie pentru ea și copii. Nu voia ca ea și copiii să fie cei care pierd totul - un cămin, prieteni, o rețea socială, familiaritate - pe lângă violență.

Așadar, Ayse a făcut așa cum a spus, deși soțul ei continua să vină la ușa casei și o amenința o perioadă îndelungată. Ceea ce i-a dat puterea și motivația de a depăși frica, de a înfrunta atacurile și hărțuirea a fost o rețea de sprijin din partea vecinilor, așa cum mi-a povestit. Nu s-a dat bătută, a obținut divorțul și a rămas în cartierul ei, unde a trăit și și-a crescut copiii timp de mulți ani.

Această poveste m-a inspirat să reflectez asupra beneficiilor comunității pentru sprijinul și siguranța victimelor. Mai târziu, am avut ocazia să lucrez în același cartier în care locuia ea și am reconstruit întreaga poveste, găsind și intervievând lucrătoarea socială locală care a jucat un rol principal în formarea rețelei de sprijin a Ayses, după ce aceasta i-a dezvăluit despre abuzul partenerului ei.

Așadar, ce au făcut vecinii?

S-au întâlnit regulat, au discutat despre situație și despre ce trebuie făcut. Unul dintre rezultatele acestei întâlniri a fost că oamenii s-au oferit voluntar să se înscrie pe o listă de telefon și au format o linie telefonică personală pentru ea. Cu consimțământul Ayses, au răspândit vestea. Într-o zi, un bărbat s-a apropiat de lucrătoarea socială, i-a înmânat o hârtie cu programul său de lucru și a spus: „Soția mea a auzit în sala de așteptare a medicului că aveți nevoie de ajutor. Mă puteți adăuga pe listă când nu sunt la muncă.”

O altă măsură a fost că, timp de aproximativ 6 luni, în fiecare zi, câțiva oameni stăteau afară, peste drum de casa ei, pentru a-i arăta soțului că este urmărit și că ea nu este singură.

Un vecin i-a reparat ușa de la intrare astfel încât să nu poată fi ușor spartă, iar ea să se simtă mai în siguranță.

Când lucrurile au devenit prea periculoase – soțul avea un pistol și, odată, a tras prin geamuri – ea a mers la adăpost, unde m-am întâlnit cu ea. În timp ce era acolo, vecinii i-au reparat bucătăria și i-au cumpărat un covor nou în culoarea ei preferată. Când s-a întors, ei o așteptau cu o măsuță de cafea, prăjitură și flori.

Astfel, oamenii din comunitate au protejat-o, au salvat-o de cheltuieli și energie considerabile legate de mutarea într-un alt loc, găsirea unei noi școli și a unei grădinițe. Astfel, ea și copiii nu au fost nevoiți să-și piardă prietenii și mediul familiar.

Unii membri ai comunității o disprețuiau pentru expunerea situației și divorț, dar un grup semnificativ de vecini din medii etnice și politice mixte o susțineau.

De asemenea, povestea ei a avut efecte colaterale. Lucrătoarea socială mi-a spus mai târziu, într-un interviu, că, pe parcursul acestor evenimente, alte persoane s-au apropiat de ea, căutând ajutor, atât victime ale violenței, cât și autori ai acesteia.